I wish I had come across Oxford Guide to Effective Argument and Critical Thinking by Colin Swatridge when I started reading ferociously and writing to a lesser extent in the 1990s. Unfortunately, Swatridge only wrote and published it in 2014. I suppose that having not found and read it for the last five years is somewhat forgivable. Nevertheless, it was a huge loss to me to have not read it much earlier.

The two main benefits of reading this book: help me to think clearly through others’ arguments and to construct effective arguments.

It might have saved me a bit from being drowned in the deluge of opinions expressed on social and political issues in recent years, some even deserving to be labelled as extreme. At times, it is tormenting to switch from working in a set of scientific domains to reading some general newspaper or magazine articles. Why is this the case? How do you derive this conclusion? Why do you think an opinion could be disguised as fact? What are your evidence for the claim here? The numerous what+why+how questions suffocate me in those occasions.

For me, it is well worth the time investment to read this book.

On arguing:

Arguing is not about winning and losing. There are no ‘model’ arguments in this book, and there are no ticks for ‘right answers’. The most that you can hope to do when you write is to persuade a reader that your conclusion is as safe and sound as you can make it for all the reasons that you give. Likewise, when you weigh up the arguments of other people it is wise neither to be too easily persuaded, nor too dismissive. You can be certain in an equation, but only rarely in an argument.

…

This is how we advance knowledge—by investigating the association between two objects. In the physical sciences, the hope is that the association between P and Q might be so strong as to amount to a law; in the social sciences and humanities, the association is more open to question.

On assumptions:

….it is best to make important assumptions explicit in your opening Statement. A statement is a standpoint: it is where you stand. Your reader needs to know where you stand….It is only a matter for worry when an assumption is implicit, for then it is, in effect, a missing reason—and it may be that missing reason that contributes most to the conclusion. Until that reason is made explicit, the argument is incomplete and may fail to persuade.

On ambiguity:

Example: argue for, or, argue against. “No one would argue that these are necessary.”, does this mean: “no one would argue against their being necessary”, or, no one would argue for their being necessary?

It matters little whether we prefer to use a word as it was used ‘originally’; what matters in a piece of writing, as elsewhere, is that we make it clear what sense it is we are giving to a word, especially if it is a word we shall be using often, or that is a key word in a subject.

On the ordering of reasons:

1. from specific to general;

2. from small to big;

3. from simple to complex;

4. from less significant to more significant;

5. from early to late (i.e. chronological order).

These are suggestions. The orders of reasons should be designed to best fit the circumstance.

After choosing and redefining the question we will answer, the author suggests to us to do the following in Chapter 2 in our reasoning:

1. avoid vagueness by defining the key terms that you will use;

2. be precise about the scope of your argument;

3. be aware of any assumptions that you may be making;

4. take care not to use ambiguous language;

5. be wary of conflating terms that ordinarily have different uses.

On arguments:

Your own argument is more likely to be accepted if you ‘tell it like it is’. Keep your claims modest, measured, even understated, and your argument will be the stronger for it, not the weaker.

Don’t make a fetish of scepticism… you will need to appeal to ‘authorities’ yourself. If they’ve written in your field, think of them as having done your dirty work; it is for you to reap what they have sown.

On appeals to feelings:

Pluses:

1. We are more immediately susceptible to an appeal to feelings than we are to reasons.

2. There are issues whose significance for us is more visceral than logical.

Minuses:

1. We can be ‘carried away’ by feelings and so neglect commonsense considerations

2. Emotion sidesteps reasoning and may make dispassionate argument difficult.

On finding weakness of someone else’s argument:

When you have settled upon your question and you have made your statement and laid out the claims and arguments assembled under Argument A, you are entitled to point out what you take to be the weaknesses (of Argument A) in that composite case:

It may be that:

1. a straw man was set up;

2. there was exaggeration or overstatement;

3. a cause-effect relationship may be suggested mistakenly;

4. a correlation may be mistaken for causation;

5. there may be misunderstanding or confusion of necessary and sufficient conditions;

6. an appeal to history, tradition, authority may be open to question;

7. likewise, an (emotive) appeal to any one of many feelings may misfire.

….By pointing out the weaknesses in the composite Argument A (without overstating them), you will lend strength to your counter-argument—if you can avoid repeating them. The chief weakness in the arguments of others may simply be that the claims made are not reasons: they are assertions unsupported by evidence; or the evidence presented is questionable. Either way, reasons and conclusion are unpersuasive.

On considering the evidence that we might present in support of our Argument B:

1. This might be in the form of examples (that will be proof against counter-examples).

2. Anecdote (bearing in mind that anecdotal evidence has its strength and weakness).

3. Facts, by discovery or by definition – both to be distinguished from factual claims.

4. If evidence is statistical, it should be clear that the sample is representative of the population under review.

5. If claims are to be credible, there needs to be evidence to corroborate them.

On certainty and plausibility: putting the terms on a continuum of knowledge, with a decreasing order of certainty: certain, probable, plausible, possible, unlikely.

Whether you are assessing someone else’s argument, then, or advancing an argument of your own, you would do well to:

1. Avoid using the word certain, other than when stating facts by definition.

2. Refer instead—and discriminatingly—to what is probable, what is plausible, and what is merely possible.

3. Engage in deductive reasoning with care, if you do so at all.

4. Be aware that conditional, or hypothetical, argument will generally yield a conditional conclusion.

5. Speak of what is true only to the extent that you can trust the evidence, the author who adduces it, and the conclusion he or she draws from it.

In Argument A, be alert to when an author is declaring a belief that may bias the argument; and note where this may lead to the expression of ill considered and subjective opinion.

In drafting your own counter-argument Argument B:

1. Be aware of bias in your own position.

2. Aim to be objective (without feeling that you have to strive for a possibly inappropriate neutrality).

3. When expressing your opinion, do so after you have marshalled your evidence, when it is more likely to be considered judgement than a prejudice.

4. Avoiding committing yourself to a principle of an absolute kind unless it meets with near-universal consent.

On examining others’ arguments and whether your argument hang together, stay alert for the following:

1. one claim might contradict another;

2. there is a danger of being inconsistent and, indeed of an argument becoming incoherent;

3. one claim does not follow from another—is a non sequitur;

4. an irrelevant point is made that may perhaps be a red herring and that may change the subject rather abruptly;

5. an argument might be circular, and when a premise may beg the question.

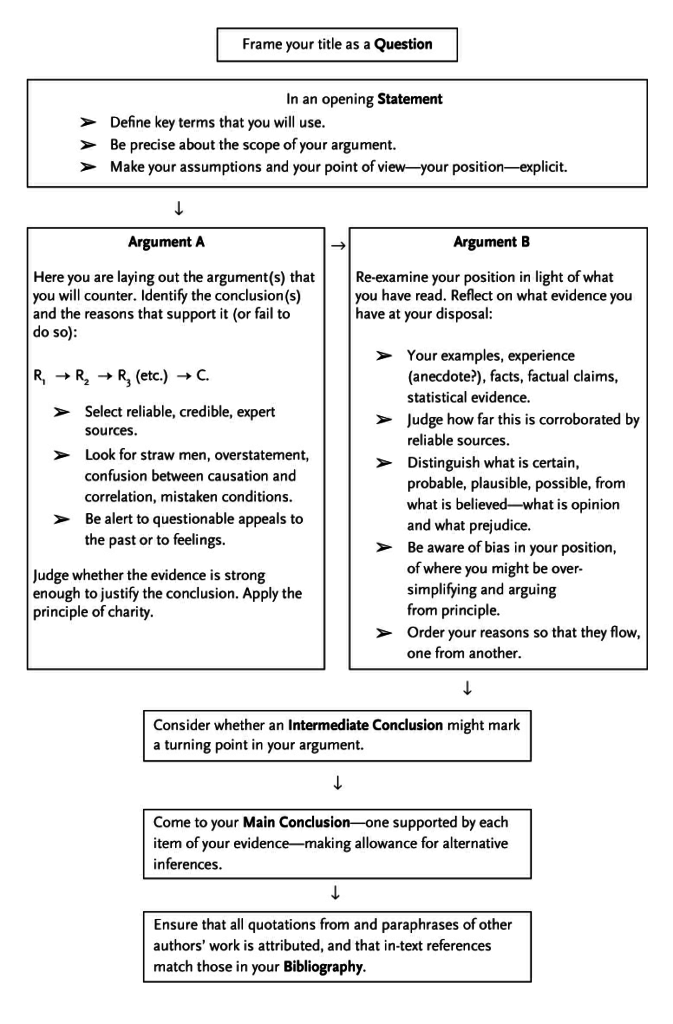

The author summarises his recommendations for effective argument in this figure below: