Matthew Siegel recommended Inventing the Truth to us. More specifically, two chapters, “Introduction” by William Zinsser & “Life With Mother” by Russell Baker were part of last week’s assignment for his course on Writing Creative Nonfiction: Fearless and Authentic Narratives. I ordered a second-hand copy. It arrived in the post on Friday evening. Brown, beautifully aged, clean with all the nice qualities of a used book but no marks that would impede the reading experience. Exactly what I want.

I miss the second-hand bookshops on Charing Cross Road and the Oxfam bookshop on Gloucester Road dearly. There was always some struggle between acquiring a nice sandwich from the Sandwich Shop on Gloucester Road to satisfy the stomach or a book in Oxfam a couple of doors down the road to satisfy the soul. Those were the best years for my soul (if I have one); it never starved.

With this nicely aged Inventing the Truth in hand, I sat down to duly read the two required chapters. Before long, I had forgotten that I did not have to go beyond those two chapters and half a book was turned. By late Sunday afternoon, it was all gone. I had a tremendously good and hard time reading it. It was enlightening and relieving to hear how these writers struggle with writing memoir, reassuring to see they all succeeded in their struggles one way or another, whatever the success means for each writer in each case.

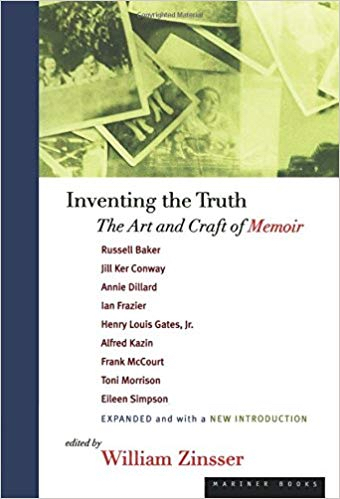

The book is edited with an introduction by William Zinsser. It has nine chapters, each of which is an account of the writer’s unique story of writing a memoir:

- Russell Baker: Life with Mother;

- Jill Ker Conway: Points of Departure;

- Annie Dillard: To Fashion a Text;

- Ian Frazier: Looking for My Family;

- Henry Louis Gates, Jr.: Lifting the Veil;

- Alfred Kazin: The Past Breaks Out;

- Toni Morrison: The Site of Memory;

- Frank McCourt: Learning to Chill Out;

- Eileen Simpson: Poets in My Youth.

It is hard to pick the favorite. If it must be done, I would pick the Introduction, Points of Departure and Poets in My Youth. “So unassertive have American women been about their identity, says Conway…, that in this century eight autobiographies have been written by men for every one written by a woman.” I applaud that Zinsser includes more underrepresented voices in this book. “Be true to yourself and to the culture you were born into, they say to all who would embark on a memoir. Tell your story as only you can tell it.”

What is a memoir? It is defined as some portion of a life. Unlike autobiography, which moves in a dutiful line from birth to fame, memoir narrows the lens, focusing on a time in the writer’s life that was unusually vivid, such as childhood or adolescence, or that was framed by war or travel or public service or some other special circumstances.

Zinsser explains the two elements that a good memoir requires: one of art, the other of craft.

The first element is integrity of intention. Memoir is the best search mechanism that writers are given. Memoir is how we try to make sense of who we are, who we once were, and what values and heritage shaped us. If a writer seriously embarks on that quest, readers will be nourished by the journey, bringing along many associations with quests of their own.

The other element is carpentry. Good memoirs are a careful act of construction. We like to think that an interesting life will simply fall into place on the page. It won’t….Memoir writers must manufacture a text, imposing narrative order on a jumble of half-remembered events. With that feat of manipulation they arrive at a truth that is theirs alone, not quite like that of anybody else who was present at the same events.

A few example passages that I enjoy from this book contain good advice for writing memoirs and perhaps even writing in general:

Forget about writing. Just Scribble, scribble, scribble, scribble. Put down anything. Write honestly. Write from your own point of view and your own voice, and it eventually takes form.

…every attempt to produce a coherent memoir amounts to falsification. No human memory is so arranged as to recollect every thing in continuous sequence, and letters and diaries often turn out to be untrustworthy assistants.

In my fast draft the writing had been timorous: I was the twenty-three-year-old girl sitting at the feet of these great men. When my editor told me to put myself in the book I began to write as the older woman I now was, not as the tentative young faculty wife. It’s an easy trap for a memoir writer to fall into, You’re trying to reconstruct something that happened when you were much more unformed, but as an artist you have to be true to the older and wiser person you have become.

The danger is self-indulgence. When you write an autobiography or a memoir you’re indulging yourself in your own sentimentality. So I found ways to guard against that: by using irony and wit and self-deprecation, and also by being honest, or revelatory, about pain and fear. Those are the techniques of a craftsman, but they’re important because a memoir is all about the unfolding of your ego, and you need to deflect your presence. You’re center stage but you need to move yourself to the periphery.

I don’t know what the legacy of my book Colored People will be. If you ask me what I would like it to be, I would like it to make younger people feel freer to tell their own stories. And I would hope that the internal cultural censor is dead. To me it was like the black inquisition.

If writing is thinking and discovery and selection and order and meaning, it is also awe and reverence and mystery and magic. I suppose I could dispense with the last four if I were not so deadly serious about fidelity to the milieu out of which I write and in which my ancestors actually lived. Infidelity to that milieu—the absence of the interior life, the deliberate excising of it from the records that the slaves themselves told—is precisely the problem in the discourse that proceeded without us. How I gain access to that interior life is what drives me and is the part of this talk which both distinguishes my fiction from autobiographical strategies and which also embraces certain autobiographical strategies. It’s a kind of literary archeology: On the basis of some information and a little bit of guesswork you journey to a site to see what remains were left behind and to reconstruct the world that these remains imply. What makes it fiction is the nature of the imaginative act: my reliance on the image—on the remains—in addition to recollection, to yield up a kind of a truth. By “image,” of course, I don’t mean “symbol”; I simply mean “picture” and the feelings that accompany the picture.

Simone de Beauvoir, in A Very Easy Death, says, “I don’t know why I was so shocked by my mother’s death.” When she heard her mother’s name being called at the funeral by the priest, she says, “Emotion seized me by the throat. . . . ‘Françoise de Beauvoir’: the words brought her to life; they summed up her history, from birth to marriage to widowhood to the grave. Françoise de Beauvoir—that retiring woman, so rarely named, became an important person.” The book becomes an exploration both into her own grief and into the images in which the grief lay buried.